Casting around in my archives, I found this, the start of a piece I wrote in 2015 about Highway 61 Revisited to mark its 50th anniversary but never published. Well, this year it turns 55, and Dylan released a new song this week, so I guess it has some kind of relevance. Guh, who am I kidding? Here’s an old thing because I couldn’t think of a new thing.

*

This August, Highway 61 Revisited by Bob Dylan turned 50. With the possible exception of A Hard Day’s Night, it’s the first true masterpiece of the rock era (by which I mean, I guess, the post-Beatles era) to reach that milestone. Which makes the record’s continuing vitality even more remarkable. Highway 61, unlike, say, The Times They Are a-Changing does not feel like a museum piece – it still explodes with life, from the very first snare crack of Like a Rolling Stone to the final refrain of Desolation Row.

Writing about this record is hard. The stories have been told and retold a thousand times (Google any one of these phrases if you want them: “it’s very tiring having other people tell you how much they dig you if you yourself don’t dig you”; “long piece of vomit”; “that cat’s not an organ player”). The songs, the lyrics in particular, have been analysed by everyone from the callowest teenage rock critic to the sagest literary professor. Normally I look for stuff that’s either less well known or something that’s not usually picked to the bone by music critics, often because it had a truly mass audience and so hasn’t been become the sole domain of Mojo and Uncut readers. What more is there to say about Highway 61, 50 years on?

Here are a few stray observations. I can’t make a coherent post out of them or find a through line, I’m afraid. They’ll have to remain disconnected little comments.

1.

Much of what has been said about Highway 61 and about Dylan in general is less than helpful. The Christopher Ricks tendency to treat Dylan as a poet rather than a songwriter divorces his words from the music and from the sound of Dylan’s voice as he performs. Most of the key pleasures of Highway 61, for me at least, are musical. The shuffle of Bobby Gregg’s drums on It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry, that crisp organ sound on Like a Rolling Stone, the interplay of tack piano and pianet, the grain of Dylan’s voice. Highway 61 is not a text; it’s vibrations in air. To receive it and interpet it solely through its words is to miss out on at least half of the experience.

2.

As an adjunct to that, Highway 61 is the best-sounding record Dylan ever made. Sure, we know he was looking for that “thin, wild mercury sound”, and that he felt Blonde on Blonde captured it better. But isn’t Blonde on Blonde a bit too thin? Doesn’t it sound weedy, placed next to Highway 61‘s big meaty snare sounds and R&B-flavoured bass?

3.

Bob Dylan was not big on rehearsing the band before they cut tracks. But if you record songs with people who are still learning them, there will be mistakes and fumbles and hesitations, and the results will have an edge, a tension, that comes from the fact that it all might fall apart at any minute.

Highway 61 has more than a few moments where the players are unsure: Gregg turns the beat around briefly in Just like Tom Thumb’s Blues. Mike Bloomfield struggles to wring more than one idea out of his guitar on Tombstone Blues. But that same approach also brought us small miracles like Al Kooper’s Like a Rolling Stone organ riff, and this rough-around-the-edges aesthetic (is there any other record where the guitars are so out of tune so much of the time?) is a huge part of what makes it charming and engaging.

4.

Highway 61‘s stylistic diversity is its strength, yet it hangs together so well as a coherent whole. Ballad of a Thin Man may take its cue, and piano riff, from Ray Charles’s gospel number I Believe to My Soul, From a Buick 6 may sound like a thousand garage-rock bands about to plug in on the West Coast, there may be a hint of Mexican cantina to Charlie McCoy’s lead guitar on Desolation Row, but the songs are a natural fit for each other, and the album is Dylan’s most satisfying long player.

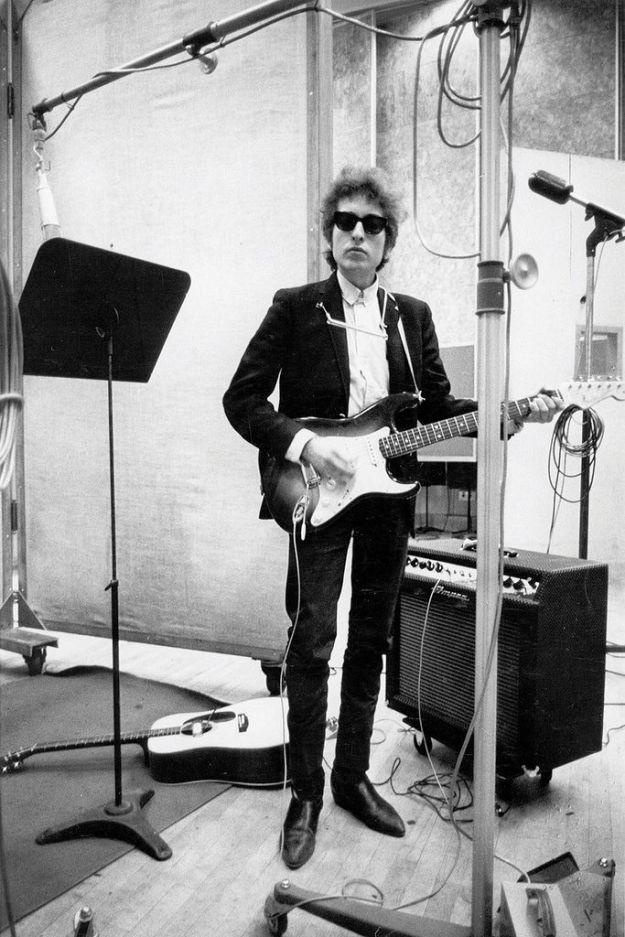

Bob in Columbia Studios, New York, 1965. Acoustic guitar lays symbolically on the floor behind our newly electrified troubadour.

If a 10-minute distraction would help right now, here’s a couple of new songs I released recently. Email me through the contact form on the About page if you’d like a Bandcamp download code.