I’ve seen Crosby, Stills & Nash. They’re groovy. All delicate and ding-ding-ding.

Jimi Hendrix

Jimi wasn’t wrong. CSN were delicate and ding-ding-ding; particularly in an era of heavy freakout records, Crosby, Stills & Nash could scarcely have sounded more different. Jimi’s own music sometimes traded sonic clarity for head-turning effects or the raw spontaneity of a captured moment. Such a mindset was pretty alien to the CSN way of working.

How did they achieve this?

When I hear the records the Crosby, Stills & Nash diaspora made together and separately in the early to mid-seventies, the word that springs to mind is lucidity. The parts are largely simple, recorded in a relatively no-fuss manner, with little in the way of trickery, and presented in mix in the most straightforward way possible. They’re bright without being cutting and harsh. They’re warm and intimate but not sludgy and ill-defined. There’s strength and muscularity there, but never in a way that overwhelms the music.

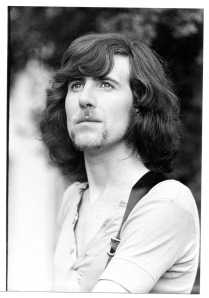

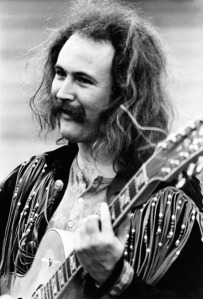

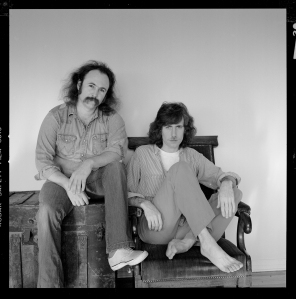

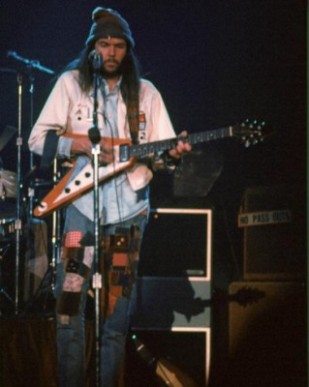

By the time Bill Halverson recorded and co-produced 1972’s Graham Nash David Crosby — by which time he’d already worked on Crosby, Stills & Nash, Déjà Vu, Stephen Stills, If I Could Only Remember My Name and Songs For Beginners — he’d got the CSN thing down to an art. There are great songs all over the album, as we discussed on Sunday, but there are also great performances and sounds. And while Halverson gives Stephen Stills a lot of credit for the sounds on the CSN debut, Stills does not play on Graham Nash David Crosby; the sounds come from Halverson and from the musicians, who as we noted the other day, comprised the very best players on the West Coast/Laurel Canyon scene: Craig Doerge, Danny Kortchmarr, Leland Sklar and Russ Kunkel; Jerry Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann and Phil Lesh from the Grateful Dead; CSNY veterans Johnny Barbata and Greg Reeves; the Flying Burrito Brothers’ Chris Ethridge and Traffic’s Dave Mason.

Doerge, Kortchmarr, Sklar and Kunkel are known collectively as the Section. When you listen to James Taylor, Carole King, Linda Ronstadt or Jackson Browne, it’s the Section you’ll hear. They were a key component of the sounds of the records made in LA for about a decade, starting in around 1971. No wonder they also called these guys the ‘Mellow Mafia’. Peter Asher had brought Kunkel and Kortchmarr in on drums and guitar for Sweet Baby James, looking for players who wouldn’t get in the way of Taylor’s vocal or intricate acoustic guitar playing. After that record’s success, the pair were involved in the recording of King’s Tapestry. Completed by pianist Doerge and the truly remarkable bassist Lee Sklar, the Section appeared as a full unit on the Jackson Browne and Nash and Crosby records, and later with Ronstadt and Carly Simon too.

On Graham Nash David Crosby, it all came together. A great group of musicians, playing strong songs and recorded by one of the best in the business at the top of his game.

Let’s look at a couple of songs. One thing you might notice listening to pre-1980s records is that the stereo image tended to be wider. There’s an approach to mixing often called LCR. LCR stands for left, centre and right. What it means is that elements within the stereo image are panned to those points only. Nothing is panned a little bit left, or a little right, or to 10 o’clock, rather than 9. There are advantages to this method. It’s bold, it clears a lot of real estate in the centre of the stereo image for the stuff that sells the song or holds it together (usually bass drum, snare drum, bass guitar, principle rhythm instrument if there is one and lead vocal), making the mix feel spacious, and it tends to provide a stereo image that feels stable even if you move around relative to the fixed positions of your left and right speakers. It’s something of an old-school technique, a legacy of an era where some mixing desks allowed you to rout tracks only to the left or right channel or both. It started to disappear a bit in the 1980s, an era where – coincidence or not – the craft of record making began its slide into the rather dispiriting mess we have today.

When you listen to say, Girl to be On My Mind, which has some fairly big drum fills from Russ Kunkel, you can hear a drum sound that appears to be a very narrow stereo (probably an XY overhead pair with close tom mics, breaking the LCR ‘rule’, panned to the positions where they appear in the overhead image), with an LCR mix constructed around it. Piano on the left, rhythm guitar on the right, bass and lead guitar in the middle, a stereo organ, and all vocals in the middle. It’s well balanced and extremely spacious. Everything has its place. It is, as I said up top, lucid, with a great sense of depth. While allowing for some lovely details – the manually ridden vocal delay at the end of the bridge for example – it’s extremely unfussy. Bold Southern European brush strokes, if you will.

Here’s the rub: a mix this good is not achievable with a half-assed arrangement. Pan LCR with an arrangement that didn’t balance in the rehearsal room and it won’t balance on record either. A lot of young mix engineers are scared of LCR mixing as they haven’t worked with musicians that give them arrangements that create this natural internal balance. Or they’ve tried to create a wide stereo mix out of two or three elements (in a sparse mix, you’ll have a hell of a time creating a coherent whole if you insist on panning the acoustic guitar out on the left and the vocal in the middle, with a mono echo on the right – but then, there are some complete wingnuts crashing around out there).

If you’re into the details of record making, and God me help I am, Graham Nash David Crosby is a treat. It sounds so good, it’s actually a little depressing hearing a modern record after it. I don’t think I’m simply romanticising the old-school methods here; I hear few records that are played as sensitively and mixed as lucidly as this now, where the details are all so clearly audible, where the sounds themselves are so rewarding. But then, I’ve never been one for a big, soupy wall of sound. I like clarity and audible detail. Halverson, Henry Lewy, Alan Parsons, Ken Caillat, Roy Halee, Tom Flye, Ron Saint Germain…

Bill Halverson