Another rainy autumn day, so wet I decided not to go for a run this morning, but to put it off till the afternoon instead. Giving me the time to write about of Island lesser-known folk revival-era artists

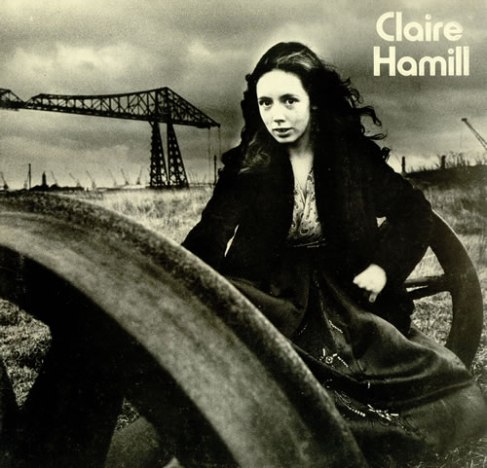

The cover of Claire Hamill’s debut album, One House Left Standing, shows the 17-year-old singer sitting on the wheel of some machine or other, while behind her stand dozens of cranes, which, far away though they may be, are plainly enormous. Heavy clouds hang threateningly overhead. It’s a striking image, contemporary and monochrome, the individual and the social context, far removed from the sort of thing one normally would expect to see on the cover of an Island Records folk album from the early 1970s. Island weren’t hugely big on making prominent social statements in their album covers back then.

Hamill, as we have discussed, was very young when her first record was released. Precocious and talented, but callow (callowness is a bit of a recurring theme with British folk-revival artists). She wore her influences on here sleeves, most obviously Joni Mitchell. She covered Urge for Going, backed by Terry Reid, Simon Kirke from Free, Tetsu Yamauchi and Rabbit Bundrick, on her first album. The Man Who Cannot See Tomorrow’s Sunshine is a dead ringer for Clouds-era Joni (being particularly reminiscent of the atmospheric medievalisms of Tin Angel). Her reading of Urge for Going, commendably ambitious though it is, is hamstrung by her inability to control her voice in its lower registers.

The Man Who Cannot See Tomorrow’s Sunshine is much more successful. Once again, it sees Hamill backed by some heavy-duty talent: John Martyn on guitar and Paul Buckmaster (the arranger most famous for his work with Elton John) on cello. That’s the benefit of having Chris Blackwell produce your album: the access to, and money to hire, the best musicians. As well as Reid, Kirke, Martyn, Rabbit and Buckminster, the album saw contributions from saxophonist Ray Warleigh, who had illuminated Nick Drake’s At the Chime of a City Clock the year before, and David Lindley, Kaleidoscope leader and longtime guitarist for Jackson Browne. Seldom will you find an album as full of great instrumental performances as Claire Hamill’s debut.

Tomorrow’s Sunshine is a strong-enough song and performance to justify the input of such stellar musicians. It was not the way of Drake, Martyn, Sandy Denny, Mike Heron or Robin Williamson to include contemporary details in their songs. Probably they were aiming at a timelessness they didn’t feel could be achieved with too many references to what was going on outside their own headspaces. Perhaps they couldn’t see outside themselves, or just weren’t interested, for reasons temperamental, emotional or chemical. The young Hamill did, and while the piling on in The Man Who Cannot See Tomorrow’s Sunshine is a little overdone (she was only seventeen, remember!), there’s a bracing streak of social-realism to a verse like this:

When he goes out on a Thursday

That’s the only day he leaves

For his unemployment benefit

And his weekly groceries

And he will never say a word

And if he does he’s never heardAnd he’s the man who cannot see tomorrow’s sunshine

Hamill never became a big star, or even an enduring cult on the level of Martyn or Reid. Instead she has a solid reputation among fans of this sort of early-seventies singer-songwriter music, but also among fans of the twin-guitar UK prog band Wishbone Ash, whom she joined as backing vocalist in the early 1980s (around the time recent recruit John Wetton, ex-King Crimson, left the band to form the chart-topping horror show Asia), and devotees of new age music (1986’s Voices was composed of layers of her voice, many of which had been sampled and heavily processed – it sounds like Enya sitting in on a Cocteau Twins b-side). She’s a minor figure compared with Denny, Martyn, Drake, Richard Thompson et al., but worth checking out for the curious.

Claire Hamill, One House Left Standing, 1971